Fighting hate: Approaches range from expanding hate crime definitions to gathering data

LOS ANGELES – Manjusha Kulkarni recognized discrimination as the norm in America when she was a fifth grader in Alabama. That realization, she said, changed the trajectory of her life.

Kulkarni came home from school to find her mother, an Asian immigrant, devastated after a job interview with a local hospital. The all-white, male panel was blunt: “Why do you foreigners come here and take all our jobs?”

Her parents filed a discrimination lawsuit with help from attorneys at the Southern Poverty Law Center, which is headquarterd in Alabama. They won.

Kulkarni called the challenge courageous, and it taught her the value of fighting injustice. So when she saw a spike in anti-Asian hate during the COVID-19 pandemic, Kulkarni chose to fight.

Kulkarni helped launch a nationwide database in 2020 to collect hate incident reports against the Asian community. As of March 2022, the Stop AAPI Hate website had recorded more than 11,500 hate incidents, which are noncriminal, bias-motivated offenses.

But only a minuscule number of these incidents – everything from physical assaults and harassment to vandalism – are reflected in federal, state and local databases and reporting systems.

Manjusha Kulkarni, executive director of AAPI Equity Alliance, sits outside her home in Los Angeles on July 6, 2022. (Photo by Jessica Alvarado Gamez/News21)

That’s because the system for reporting hate in America is broken: Hate crimes and incidents are severely underreported and misunderstood. The FBI’s database of hate crimes has limited scope, and people across the country won’t – or sometimes can’t – report to law enforcement when they become a target of hate.

Without a true understanding of what’s happening, to whom, how often and where, it’s difficult to address hate crime and stop it, experts say.

But Kulkarni isn’t alone in her fight. Federal, state and local entities are tackling hate in America in a variety of ways – from changing the definition of what constitutes hate to forming partnerships to better support victims to launching hotlines to capture more robust data.

There’s no silver bullet against hate, but experts agree communities need to take a multipronged approach to ensure hate is reported, analyzed and resisted – and that requires collaborating, building trust and raising awareness.

As activists and others push for police reform across the country, hate crime reporting doesn’t always make it to the top of the list of most-critical reforms. But those who study hate say maybe it should.

The U.S. Department of Justice lists eliminating acts of hate as one of its highest priorities. And experts say each hate act hurts more than just the individual victim, it sends an ominous message to whole communities.

“Hate crimes are message crimes. Hate crimes send a message to not only the victim or the victim’s family, but the entire community,” said Ariella Loewenstein, deputy regional director of Anti-Defamation League Los Angeles. “It says, ‘You’re not welcome here. You’re not safe here. We don’t want you here.’”

Definitions of hate vary widely

What is a hate crime? Depends on who you ask.

In August 2020, a man approached Hong Lee as she waited for tacos in a Los Angeles restaurant. The man asked her to have lunch with him. After Lee – a wedding ring on her finger – declined the offer, the man told her to go back to Asia, using racial slurs and other derogatory terms.

In a panic, Lee hit the record button on her phone, then did what most Americans do when feeling endangered: She called 911.

A police officer arrived, watched the video and told Lee the man didn’t break any laws. There was nothing they could do. Under the First Amendment, the man had the right to say those words.

Soon after, Lee began to speak out. She posted the video on social media, and it went viral, earning more than 21,000 likes and 5,000 comments on Instagram as of September.

After the incident gained so much attention, Lee said, Los Angeles police finally took action. They took a police report, classifying the encounter as a hate incident.

Los Angeles is among the few departments in the country that even have that option. Some departments won’t take reports on noncriminal hate incidents, much less track them.

The federal definition of a hate crime is a criminal offense motivated, in whole or in part, by the offender’s bias against protected groups, including race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity and disability.

Many states – and many cities – have their own definitions.

That’s a challenge, said Michael Jensen, senior researcher at the University of Maryland’s National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism.

In addition to adopting a universal definition, Jensen said, the country would need to deploy it at the federal, state and local levels to collect consistent data, adding, “That’s a pretty tough thing to do.”

Under a federal hate crime law adopted in 1990 and updated in 2009, the FBI must track hate crimes. However, it’s voluntary for police departments to collect and submit their data to the national database.

Most don’t.

The reasons vary: The system isn’t always clear or easy. Some department leaders don’t see the need or want the stigma attached to reporting hate crimes in their community. And sometimes, officers don’t even know how to properly identify bias-motivated crimes according to their state laws.

“Despite the fact that the FBI over the last 30 years has tried to do considerable training throughout the country to get everyone on the same page, there still seems to be a lot of confusion at the state and local level over what should be reported and what shouldn’t,” Jensen said.

Orlando Martinez, the hate crimes coordinator for the Los Angeles Police Department, said he has witnessed severe underreporting of hate crimes in his more than 23 years as an officer in one of the country’s biggest cities. Last year, the city reported 615 hate crimes, which Martinez called “statistically improbable.”

It’s worse on the national scale.

“Across the nation, departments are counting zero,” he said. “‘We had zero. We had zero consistently for decades.’ They hadn’t had any hate crimes, which is statistically impossible. But that’s what they’re reporting.”

Among the 15,138 law enforcement agencies that submitted data in 2020, 88% reported no hate crimes at all, according to Brian Levin, the director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, who was quoted in an article from Axios.

For example, Alabama, with a population of nearly 5 million, reported zero hate crimes in 2019. Martinez said that’s statistically impossible.

Jensen said a potential solution “everybody would like to see” would be a federal requirement that states and local jurisdictions participate in the FBI reporting. However, that’s not likely.

“That would take an act of Congress,” he said. “And right now, that feels like it would take an act of god for Congress to get on the same page and to do something like that.”

President Joe Biden said he recognized the lack of resources and training for law enforcement to identify and report hate crimes to the FBI. In May 2021, Biden signed the COVID–19 Hate Crimes Act. Among other actions, the Department of Justice will issue clearer guidances for law enforcement to establish online reporting of hate crimes.

Maureen O’Leary, director of field and organizing at Washington, D.C.-based Interfaith Alliance, said the act is something “we have needed for a long time.”

“It’s a first step, but it is only the first step.”

States and cities can strengthen laws

Many states, especially those with large, diverse metropolitan areas, have gone even further by increasing penalties, broadening protection to include additional identity classes and requiring more accurate data collection.

For example, Oregon passed a comprehensive bill in 2019 that brought landmark changes to the state’s existing hate crime law. Senate Bill 577 extended the definition of a hate crime to include gender identity, tightened data collection requirements and eliminated hard-to-meet state mandates, such as requiring two or more people to commit the crime to be classified as bias-motivated in the first degree.

Sixteen other states protect gender identity. Thirty-four do not, according to data from the U.S. Department of Justice.

Three states – Wyoming, South Carolina and Arkansas – don’t have any additional protections against bias-motivated hate.

It’s been more than two decades since the killing of Wyoming native Matthew Shepard – a murder that bears the name of the 2009 federal hate crime law and inspired state laws across the country.

Jim Ritter, a consultant who specializes in improving relationships between law enforcement and LGBTQ+ communities, said even though the Shepard case made national news, Wyoming didn’t pass its own hate crime laws.

“Look how many years and how many victims have probably continually been assaulted in Wyoming or other states,” said Ritter, a retired LGBTQ liaison with the Seattle Police Department. “There’s something that the legislatures in the states can do about it. But until they have a reason to, they won’t. And the federal government can’t force them to.”

Even when states don’t have their own hate crime laws, cities can make changes to strengthen their ordinances. For example, in South Carolina, the Charleston City Council passed a hate intimidation ordinance.

Officer training plays key role

Reporting of a hate crime often hinges on the individual officer’s ability to properly identify a hate crime per state guidelines. The Uniform Crime Reporting program only accounts for prosecutable hate crimes reported to local police departments.

“The reality of it all, across the nation,” Martinez said, “is that people don’t call the police saying, ‘I need help. I’ve been the victim of a hate crime.’ People call because they get hurt, they’re scared and threatened.”

It’s up to the training the officers receive to recognize these bias-motivated events, Martinez said. If departments don’t require training or don’t make it a priority, some, or most, of these events will go unreported.

A 2018 Bureau of Justice Statistics survey of nearly 770 training academies across the country found most agencies reported some hate crime training to recruits, averaging fewer than five hours. Only 5% of the academies devote two days or more to the topic, according to a News21 analysis of the data, the most recent available.

Some departments partner with outside agencies to conduct training.

For example, Not in Our Town, a program to stop hate, offers online courses on topics such as transgender issues. The Bureau of Justice Assistance has offered funding to support the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Program, which also conducts training.

Senior Officer Terry Cherry, the recruiter for the Charleston Police Department, said the Matthew Shepard Foundation and Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law collaborated with them to do a voluntary hate crime training – especially important because of the city’s hate intimidation ordinance. She said she tied the training to LGBTQ+ and social justice issues, which she’s passionate about improving.

“I had a really good turnout because it wasn’t mandatory,” she said, adding that officers told her privately how much they wanted the training.

The Anti-Defamation League, a 109-year-old organization based on Jewish values, said it educates an estimated 15,000 law enforcement personnel every year. The league partners with police agencies to educate officers on the damage of anti-Semitic vandalism, slurs and attacks.

In one of these trainings, in Los Angeles, the league brought in a rabbi to provide a history and culture lesson so LA police could develop better practices when interacting with the Jewish community.

With better knowledge and understanding, Loewenstein said, law enforcement can respond with support and care, and then the whole of society can follow.

A news outlet described the 2018 ordinance passing with “little public discussion or fanfare” – with less debate than on Charleston’s proposed plastic bag ban. But city leaders said they felt it was time for the city to go after acts of targeted violence, according to Charleston City Paper.

At the time, the police chief said he hoped a state hate crime law would follow. So far, it hasn’t.

Jimena Sandoval, communications and marketing coordinator for TransLatin@ Coalition, stands in the organization’s drop-in center in Los Angeles on July 5, 2022. (Photo by Jessica Alvarado Gamez/News21)

Why people don’t report: trust

Inside the TransLatin@ Coalition’s office in downtown Los Angeles, a poster on a yellow wall shows a dark-skinned woman striking a pose like the Statue of Liberty. It reads, “Trans is beautiful.”

The hum of a small television with a Spanish morning talk show plays in the background. Photos of clients make up a collage with golden lettering that reads “Mis Hermanas, Mi Familia.” My sisters, my family.

Alexandra Magallon, coordinator of policy and community engagement at the TransLatin@ Coalition, said there’s a fractured relationship between police and marginalized communities.

“I was assaulted, raped and drugged in Hollywood in 2020,” Magallon said.

When she finally found the strength to report to police, it didn’t go well. She felt her identity as a brown, transgender woman made officers assume she was doing something criminal.

“When I went to file a report, they didn’t want to take my report,” Magallon said. “They were like, ‘Was this a client? Were you doing sex work? Were you doing X, Y and Z? There is no way you could have been raped, you are trans.’”

She told her story over and over, and the evidence later proved she was telling the truth, she said.

“It’s these types of things and incidents that push for underreporting, especially in Black and brown communities,” Magallon said.

Alexandra Magallon, who is a coordinator of policy and community engagement at the TransLatin@ Coalition, shares her experience with hate in Los Angeles on July 5, 2022. (Photo by Jessica Alvarado Gamez/News21)

The number of crimes that go unreported is known as the “dark figure” of hate crime. In a 2019 report, hate crime researcher Frank S. Pezzella noted the disparities between the National Crime Victimization Survey and the Uniform Crime Reporting program.

Although both are nationwide data collection methods, the victimization survey reported 269,000 victimizations from 2004 to 2012, while the FBI’s database reported an average of 8,770 incidents in the same time period, indicating considerable lack of reporting, Pezzella found.

The Bureau of Justice Assistance noted in a hate crime fact sheet that victims often don’t contact law enforcement for a variety of reasons: distrust of police, language barriers, concerns about immigration status.

Groups such as TransLatin@ Coalition exist, in part, to help fill those gaps in the reporting system. The coalition, a nonprofit led by a team of transgender women, makes resources accessible for LA’s transgender Latinx community.

Anti-violence case manager Angelika Carrillo helps clients fill out police reports and educates victims about their rights.

“You don’t feel like you’re being treated right? Ask for a sergeant,” Carrillo said.

“It’s never too late to report, and I’m there to make sure that they’re treated fairly,” she added. “Once they have that support, it’s like a little personal backbone for them.”

Some state leaders have recognized the need to improve relationships with communities.

Oregon’s 2019 hate crime law required the state’s Department of Justice to set up a Bias Response Hotline, which launched in 2020. It’s one way to encourage people to report incidents without having to go directly to law enforcement.

Trained advocates, not police personnel, staff the hotline. Operators can connect callers to such services as local mental health services, advocacy groups and emergency financial assistance.

“The hotline is a confidential space that’s not law enforcement for folks to report bias, whether it’s criminal conduct or non-criminal conduct,” said Johanna Costa, the hotline’s civil rights coordinator.

The hotline received more than 1,600 reports in 2021, a 53% increase from the previous year, according to the most recent annual report.

Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum called the numbers discouraging in a statement announcing the report’s release but said she’s pleased the state has stepped up its outreach and made reporting more accessible.

Costa said the overall goal of the hotline is “to center the survivor and not center the perpetrator.”

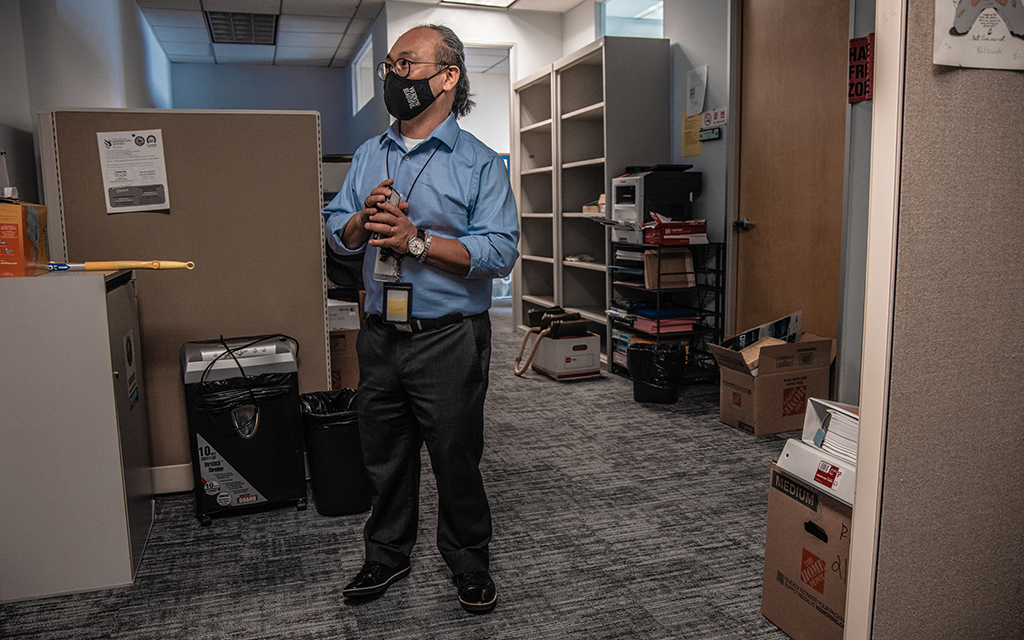

John Kim of Asian Americans Advancing Justice says one major problem is law enforcement agencies and other organizations still are learning how to deal with hate crimes. People try to report to the police, Kim says, but nothing happens to resolve the issue. (Photo by Jessica Alvarado Gamez/News21)

Why people don’t report: Language

Oregon’s hotline offers interpretation in more than 240 languages, and the Oregon Department of Justice’s website is available in nine languages.

“On the hotline, all of our advocates are bi- or multilingual and bicultural, and they are bringing such energy and an important perspective and lens to this work,” Costa said.

Other organizations focus on bridging the language barrier.

In downtown Los Angeles, the sound of scattered phone calls ring out in the office of Asian Americans Advancing Justice, a national organization that provides legal counseling and other resources to Asian Americans.

In 2002, the office established a multilingual helpline for community members to report any incident of hate, criminal or not. Responders speak several languages, including Mandarin, Cantonese, Thai, Tagalog, Korean, Hindi and English.

Once callers give their report via the helpline, workers direct them to resources such as therapy, medical assistance and legal aid.

“A lot of times, people don’t know what their rights are” said John Kim, lawyer and managing director of client services. “It’s unfortunate, and we’ve been trying to educate people more on that.”

Kim said his group also helped develop a “know your rights” resource card in 26 languages. Developed in coordination with other groups, Los Angeles Police Department’s officers agreed to hand these out to victims and bystanders. The cards include definitions of various acts of hate and why it’s important to report the offenses, as well as phone numbers of organizations that offer culturally specific victim support service.

A man walks outside the Garvey Park Gym in Rosemead, California, in September 2022. Artist MariNaomi created the mural to raise awareness about violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. (Photo by Emeril Gordon/Special for News21)

Groups try to raise awareness

The mural by graphic artist and renowned cartoonist MariNaomi stretches across a building in LA: “Together we are stronger. Stop Anti-Asian Hate!”

She said she wanted to get the word out about 211 – a hotline in LA to report hate incidents – provide some history and “to tell my story and maybe give a little hope.”

MariNaomi had partnered with LA vs Hate, a campaign focused on cultivating a community against hate, for the initial mural in Rosemead. It was so popular, the campaign commissioned two additional-large scale murals and posters with the comic strip were pasted throughout the county.

In Los Angeles, the County Commission on Human Relations has used the work of MariNaomi and other murals, nail art and social media to raise anti-hate awareness. The commission formed LA vs Hate in 2019 and revived it through the 2021 American Rescue Plan.

Since it began, the program has collaborated with more than 100 organizations to discuss anti-hate strategies, contracted with the 24/7 helpline in 140 languages to track and report acts of hate and launched an advertising campaign.

MariNaomi shared a story about the mural’s impact, saying a man and woman had been attacked at a park by an individual yelling hate slurs at them. At the mural’s unveiling, the man spoke about his experience said the mural made him feel safer. “He felt more welcomed, and he’s not afraid to go the park any more,” MariNaomi said.

LA vs Hate is one of the first, and few, all-inclusive anti-hate programs implemented across a county in the U.S. Other communities can recreate all aspects of their efforts, program coordinator Theresa Villa-McDowell said.

Hong Lee, whose video went viral, has become an ambassador for LA vs Hate. She shares her story, speaks at events and posts on social media, saying such things as, “We will continue to fight against normalizing hatred.”

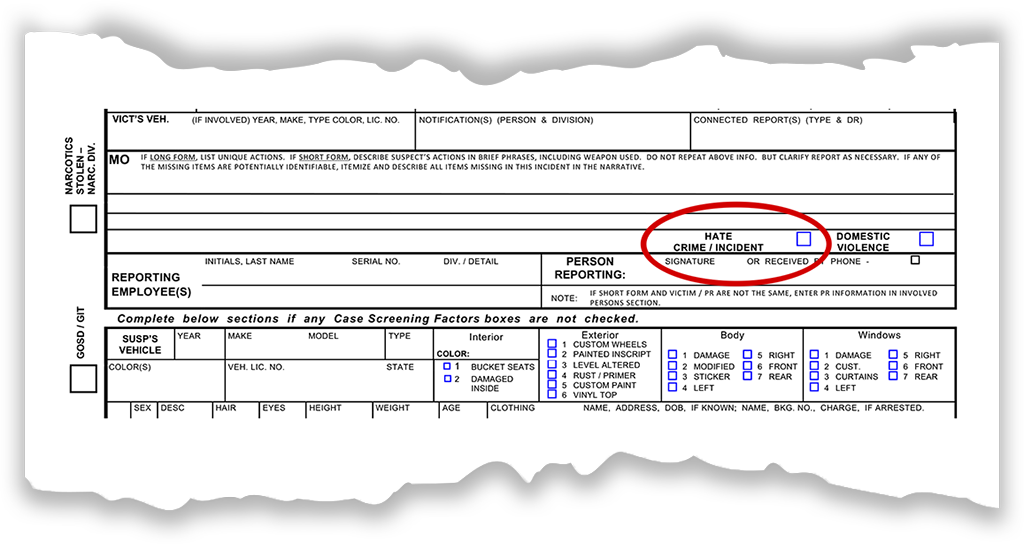

Keeping hate top of mind is one of the reasons the Los Angeles Police Department changed its police reports. First-responders can check a new box at the top of the form to indicate that bias fueled the incident. The checkbox, approved in 2021, says “Hate Crime/Incident.”

“This check box is a quick and easy way to identify bias-motivated events for those seeing the report without having to read the entire narrative,” Martinez said.

Even if they aren’t official crimes, it’s still important to take reports of non-criminal incidents to collect evidence of patterns on offenders in case their acts of hate escalate, Los Angeles County hate crime coordinator Justin Cham said.

“We will continue to fight against normalizing hatred.”

– Hong Lee, ambassador for LA vs Hate

Fighting hate in the long term

Cham said information is the most scarce resource when it comes to hate incidents and crimes.

Until recently, communication between departments about hate crimes or incidents hadn’t been fluid, Cham said. But now, the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, the FBI and several local agencies collaborate to combat hate. They call it the L.A. Hate Crime Task Force.

Cham said their ultimate goal is to grow the task force to include all law enforcement agencies in the county so they can share information, recognize patterns and identify suspects.

“Maybe they have different information than we do,” Cham said. “Maybe they have a vehicle or, you know, a residence or their name. We can stop the ones happening over here just because we’re cooperating, collaborating with other agencies that are having the same issue.”

Because that information is so important, it can sometimes get tricky when hate incidents get funneled through a third-party, such as a community organization.

Cham said the information doesn’t always make it to police and important details – such as a suspect description – can’t help law enforcement unless they have it. Cham said the task force’s goal is to take attackers off the streets before they can victimize anyone else.

But Kulkarni, whose Stop AAPI Hate organization does allow people to report information anonymously, said the data matters.

“Our data shows what’s happening day in and day out,” said Kulkarni, who also serves as executive director of AAPI Equity Alliance. “It’s not just those murders or the physical attacks. It’s what happens every single day.”

Incidents on Stop AAPI Hate’s reports range from verbal hate speech to the 2021 fatal shooting of eight at three Atlanta-area massage businesses.

This data provides a holistic view of hate in America and where it happens, Kulkarni said.

For example, the group noted more than three quarters of hate incidents against Asian American Pacific Islanders in California took place in person and in spaces accessible to the public – public streets and sidewalks, public parks, public transit, with many other incidents happening in businesses, such as grocery stores and restaurants.

The group worked with legislators to introduce No Place for Hate California, which includes a bill that would expand civil rights protections at large businesses and one that would require the largest transit operators to address hate-based harassment of riders.

Kulkarni said information Stop AAPI Hate tracks can help policymakers and law enforcement understand the need for change, better allocate support where it is needed and fund resources for communities in the greatest need.

Although big cities like Los Angeles may have access to funding and resources to organize big campaigns such as LA vs Hate, some cities and towns might struggle to find resources for similar endeavors. But many organizations offer online tools and resources.

Some efforts to fight hate focus on prevention – starting with children.

The Southern Poverty Law Center, which offers resources to K-12 classrooms across the country, said bias is learned in childhood: “By age 12, they can hold stereotypes about ethnic, racial, and religious groups, or LGBT people. Because stereotypes underlie hate, and because almost half of all hate crimes are committed by young men under 20, tolerance education is critical.”

Experts who study the issue agree that even though the numbers might not show it in every community across the U.S., the need to fight hate is pervasive.

“So while there is some difference between communities and geographic regions across the country, really this kind of hate is universal,” O’Leary said. “These conversations we’re having are countrywide and the dangers are countrywide. Nobody is immune to them.”

News21 reporters Mikayla Roberts, James Doyle Brown Jr. and Cronkite News reporter Hailey Forbis contributed to this article.

Top photo credit

A chalkboard filled with drawings of staff and a large rainbow hangs near the front desk at the TransLatin@ Coalition office in Los Angeles on July 5, 2022. Jimena Sandoval, the group’s communications and marketing coordinator, says it was drawn for Pride Month. (Photo by Jessica Alvarado Gamez/News21)