(Video by Gabriela Tumani/News21)

‘Here for everyone’: Police in Colorado town use outreach, TikTok to gain immigrants’ trust

AVON, Colorado – Alan Hernandez wanted to be a police officer his entire life.

Born in Zacatecas, Mexico, he came to the U.S. when he was 4. But when Hernandez approached the Avon Police Department to volunteer when he was 15 years old, the answer was no.

The department couldn’t work with Hernandez because of his immigration status, he said.

Hernandez persisted. He got his permanent residency and – eventually – a job as a police officer. Today, Hernandez is a detective in this small Rocky Mountains community, just a few miles west of the well-known ski town of Vail.

Hernandez said he uses his experience to better connect with Avon’s large immigrant community. Nearly a quarter of the town’s 6,000 residents were born outside the U.S., and nearly 40% identified as Hispanic or Latino, according to the latest U.S. census.

“They always tell me they are scared to go to the police,” Hernandez said in Spanish. “That it is easier for them to speak to a Spanish-speaking officer who maybe understands their immigration status and understands the battles they have to fight.”

Across the U.S., immigrants make up roughly 14% of the population, nearly triple the share in 1970, according to Pew Research Center.

Immigrants’ perceptions about police are “complex and subjective,” depending on a variety of factors, academic studies have found. A recent study published in the Academic Emergency Medicine focused on Latinx patients in emergency rooms – both documented and undocumented – who were asked about crime victimization. Both groups said they were afraid to report crimes to police.

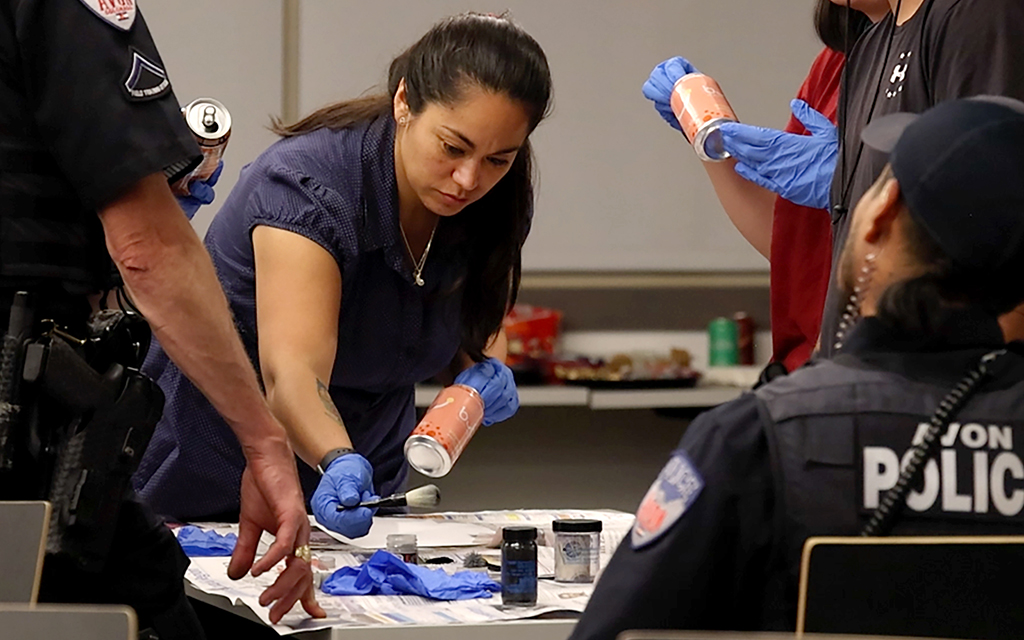

Left: Daniela Rodriguez dusts a soda can for fingerprint evidence while participating in the Latino Police Academy in Avon, Colorado, in July 2022. The Latino Police Academy is an eight-week course designed to educate and familiarize residents about police procedures. Right: Community members listen to presentations at the Latino Police Academy in Avon, Colorado, on July 11, 2022. The purpose of the academy is to educate and inform the Latino community about police procedures in the small Rocky Mountain city. (Photos by Gabriela Tumani/News21)

Top: Daniela Rodriguez dusts a soda can for fingerprint evidence while participating in the Latino Police Academy in Avon, Colorado, in July 2022. The Latino Police Academy is an eight-week course designed to educate and familiarize residents about police procedures. Bottom: Community members listen to presentations at the Latino Police Academy in Avon, Colorado, on July 11, 2022. The purpose of the academy is to educate and inform the Latino community about police procedures in the small Rocky Mountain city. (Photos by Gabriela Tumani/News21)

Law enforcement agencies nationwide have launched efforts to engage with immigrant communities through language and cultural programs in hopes of building trust. Some practices highlighted in a Police Executive Research Forum report include training officers on cultural competency, developing a unit to coordinate interpreters and encouraging officers to speak on Spanish-language radio.

In Avon, the department has hosted a Latino Police Academy – or Academia de Policía Para Latinos – for about a decade. Seven of the department’s 21 officers speak Spanish. And officers have posted fun TikToks in Spanish as a way to connect with immigrants.

Hernandez participates in all of it, including the TikToks. He wants to dispel the myth that if you don’t have legal residency, you can’t trust police.

“A lot of people think it’s a service that is only for residents or citizens,” he said. “But no, the police are here for everyone.”

Chief Greg Daly said his department’s No. 1 priority when responding to calls is addressing the issue at hand, not a person’s immigration status.

Some residents won’t report crime, he said, because of their “concern that there would be immigration ramifications from that report.”

(Audio by Natalie Skowlund/News21)

“It is absolutely irrelevant to us as to what their immigration status is when we arrive,” he said.

For people like Laura Segura, an organizer with the Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition who works closely with Latino communities in Colorado’s mountain towns, that’s not always clear.

Segura’s eyes welled up while recounting the times her son worried she would get pulled over while driving. Without the proper papers, she couldn’t get a valid driver’s license.

And her fears run deeper than getting a citation during a traffic stop.

Segura, who was born and raised in Mexico City, said most officers in Mexico’s capital city were corrupt – a corruption she contends exists in this country as well.

She said migrants coming from other countries often expect to feel safe here, but sometimes don’t.

“Our public safety departments are not providing safety,” she said in Spanish. “That worries me.”

She agreed, however, that engaging with the immigrant community could improve the relationship with police.

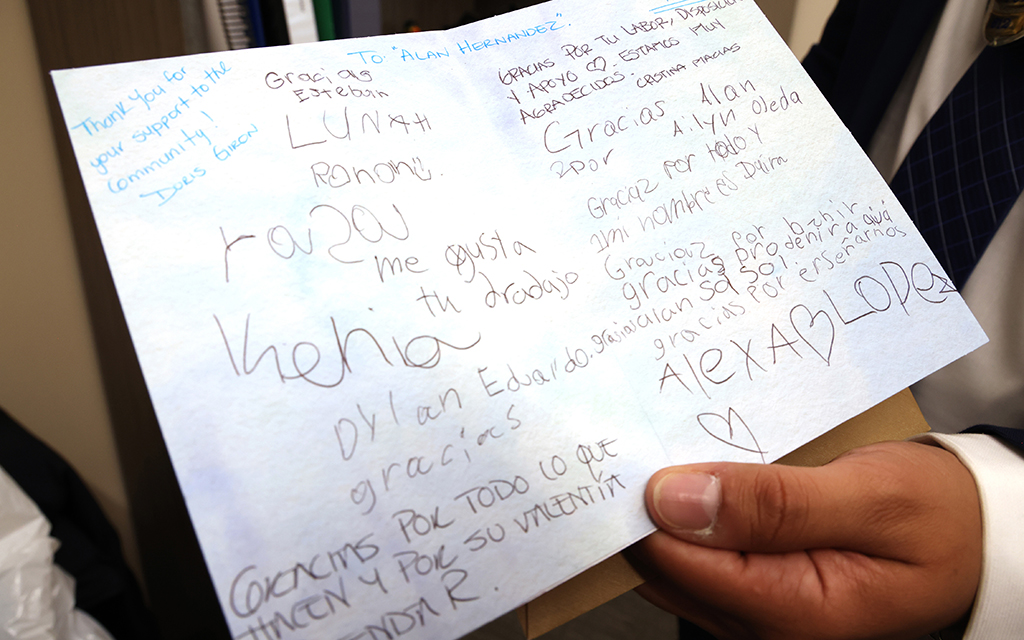

Left: Detective Alan Hernandez of the Avon Police Department uses his experience to connect with the small Colorado city’s large immigrant community. Photo taken in July 2022. Right: Detective Alan Hernandez of the Avon Police Department holds a thank you card he received from members of the Latino community in Avon, Colorado. Hernandez says reaching out to connect with the community is essential to building trust. Photo taken in July 2022. (Photos by Gabriela Tumani/News21)

Top: Detective Alan Hernandez of the Avon Police Department uses his experience to connect with the small Colorado city’s large immigrant community. Photo taken in July 2022. Bottom: Detective Alan Hernandez of the Avon Police Department holds a thank you card he received from members of the Latino community in Avon, Colorado. Hernandez says reaching out to connect with the community is essential to building trust. Photo taken in July 2022. (Photos by Gabriela Tumani/News21)

That’s the goal of the Latino Police Academy, an eight-week course to educate and familiarize residents with police procedures. More than 20 people attended the first session in July.

Using soda cans and fingerprint kits, Avon police officers and detectives showed residents how to dust for evidence. In later sessions, participants were scheduled to practice self defense techniques, experience a virtual simulation on use of force and learn how to identify an impaired driver.

Daly said these types of interactions can help “close the gap” between officers and residents.

“We hope that by the end of these eight weeks, you’ll consider yourselves our friends,” he told the participants.

Daniela Rodriguez, a resident of nearby Edwards who came to the United States from Chile in 2009, said she felt small next to officers wearing tactical gear and carrying weapons.

Rodriguez has long had a negative image of law enforcement.

But four years ago, she said, officers helped her at a time when she was suffering from addictions and alcoholism.

“I was seen,” Rodriguez said. “For me, that made me feel valued as a human being.”

Rodriguez said attending the academy made her see the officers as human beings as well.

“There is still fear in the community,” she said. “But these academies are helping.”

Diannie Chavez is a Buffett Foundation Fellow. Gabriela Tumani and Natalie Skowlund are an Inasmuch Foundation fellows.