(Video by Reagan Creamer/News21)

‘De-escalation training,’ culture change may lead to less deadly encounters

INDIANAPOLIS – Police in America are turning toward training and cultural changes to de-escalate deadly encounters, with police leaders, lawmakers and activists enacting reforms in several U.S. cities.

Researchers say police departments are conditioned to approach traffic violations, mental health calls and other routine interactions in ways that keep officers safe but too often positions members of the public as potential threats.

However, according to University of Cincinnati researcher and criminologist Robin Engel, “evidence now exists that de-escalation training can make police encounters with the public safer for all.”

Adrenaline-fueled encounters have led to tragedy, often after traffic stops and mental-health calls.

The Georgia State Patrol in April agreed to pay $4.8 million to the family of Julian Lewis, who was shot to death in 2020 after a traffic stop and car chase.

The Rev. David Greene preaches at the Purpose of Life Ministries in Indianapolis on Sunday, July 10, 2022. “Those things didn’t exist until recent years,” he says of recent police reforms. “And it’s because the community said, ‘Hey, we need changes in this area.’” (Photo by Mikey Galo/News21)

The State Patrol had one hour of de-escalation training in 2018, according to information it reported to Bureau of Justice Statistics data. Across the country, the vast majority of police training academies have fewer than two hours of training, according to an analysis of federal data from 2018, the latest available.

“It certainly seems that this was an instance where the trooper lost his temper,” said Andrew Lampros, an attorney representing the Lewis family who thinks de-escalation training would have made a difference. “Mr. Lewis was not a threat to anyone.”

Researchers and advocates say proper de-escalation training can reduce violent encounters between police and the public. But even as some experts cite de-escalation as one of the most demanded police reforms, there are challenges that limit its implementation on a national scale.

Community activists say training won’t prevent police killings, and it needs to be matched by cultural changes from police, city and state leaders. Standards for de-escalation – and what the term actually means – also are unclear. Often, it’s dependent on leadership that may change and limited research into effectiveness. A perceived risk to officer safety also is a barrier to de-escalation.

Still, as more police encounters in the U.S. turn deadly, supporters say de-escalation points toward an imperfect but necessary way to reform.

In Indianapolis, a coalition of police officials and community activists worked to expand de-escalation training, which now is among the most extensive in the country. The Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department provided 232 hours of de-escalation training for its recruits in 2018, according to the Census for Law Enforcement Training Academies.

De-escalation in Indianapolis

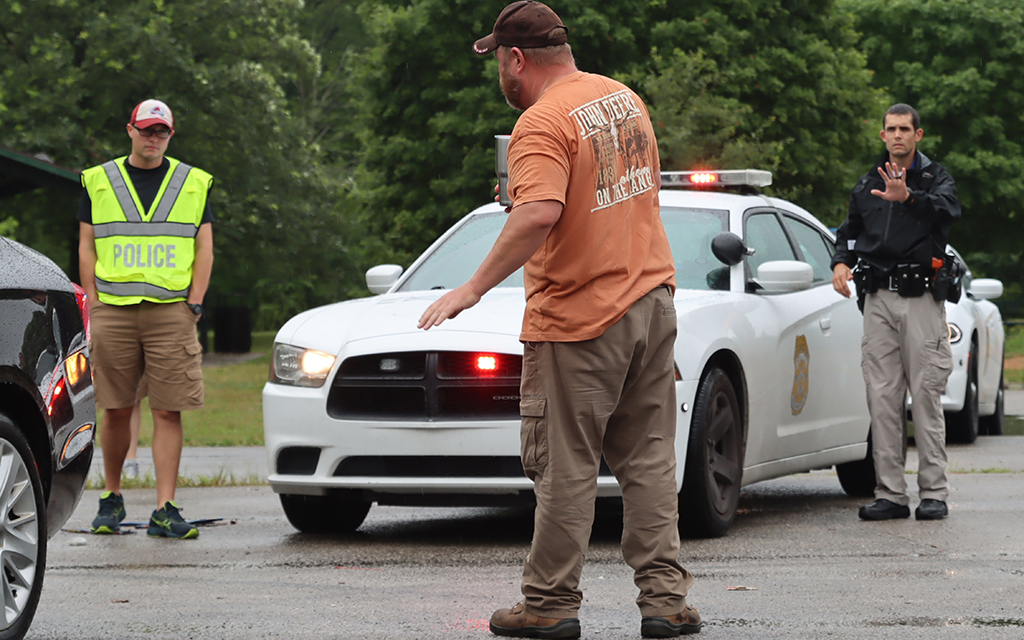

On a wet Sunday in early July, police recruits pulled over cars driven by field training officers, with future officers placed under pressure and the watchful eyes of experienced officers as they navigated traffic stops. Some of the unscripted interactions were routine and cordial. But there also were highly volatile, high-stress situations that officers face routinely.

That’s where mistakes were made.

Training officers for the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department call this daylong exercise Unknown Traffic Stop. Experienced officers hover nearby, correcting behavior that could leave someone dead.

Time and again, they teach.

You’re talking to the driver beside the open front door of the car – don’t put him between you and the gun in the console.

Don’t interpret a frantic man waving his arms as a threat when he may be in a tough situation, needing your help.

And never forget to communicate with fellow officers on scene.

Kevin Hershberger, a field training officer, called Unknown Traffic Stop “reality-based training” that mirrors the “99% of calls that do not require force.”

“When I came on, scenario-based training was all about coming out and messing with recruits,” said Hershberger, who started field-training work 20 years ago. “Every role player had guns on them, and every role player had drugs all over them and stuff like that. Every scenario you went into was ‘Bang, bang, you missed this gun. You’re dead.’ It was never a winnable thing.”

Indianapolis police de-escalation training scenario: A gun in the car

Two recruits in separate police cruisers stop a black Chevrolet Impala after it rolls through a stop sign. But when the recruits approach the sedan – one on each side – and introduce themselves to its two occupants, they see a pistol resting in the center console. When the driver denies having a weapon, the recruits tell the pair to keep their hands in plain sight and exit the vehicle. The recruits determine the pair are unlawfully carrying the weapon and arrest them. (Text by Mikey Galo/News21)

What went wrong

The driver leaves the car and a recruit pats him down next to the open front door.

“So, is this a quick pat down?” a field training officer asks the recruit, who stops and turns around.

“You’ve still got him between you and the gun,” the training officer says.

Immediately, the recruit grabs the driver by the arm and guides him to the back of the car. No violence occurs.

What went right

When the recruits see the handgun, they don’t reach for their weapons but instead talk with the driver and passenger.

“Keep your hands on the steering wheel,” one says.

She looks to the other recruit on the passenger side, who has already told the passenger to keep both hands on the front-seat grab handle. That recruit looks back at her and nods.

“OK, I’m opening the door now,” she says as the driver exits. The recruit does the same with the passenger. No weapons are drawn.

Catherine Cummings, deputy police chief of training, policy and oversight, said Indianapolis has made a number of changes since 2020, including converting its firearms board into a civilian-led use-of-force board and adopting a newer training model for de-escalation.

De-escalation is built into the department’s DNA, Cummings said.

“We were already very steeped in de-escalation training prior to 2020,” she said. “And so we just looked at what is out there, what additional training we can add to what we’re already doing – just make sure that our training is keeping up with current demands and what is considered best practice across the country.”

The department, which also is involved in a research project at the University of Cincinnati, started training veteran officers this year and will continue next year, Cummings said.

“Any time that we feel that we need to do kind of a refresher in in-service training for veteran officers, we will do that as well,” she added.

The key to de-escalation, Cummings said, is communication.

“The fact that your tone, your physical presence, your facial expressions, all of that matters when you’re talking about de-escalation,” she said. “We’re teaching them to do something that they do with their own families and their own friends and their own neighbors every single day.”

Indianapolis police de-escalation training scenario: Passenger has a mental health crisis

A police recruit stops the black Chevrolet, which has swerved across the center line. The recruit believes the driver, who exited the sedan as soon as it stopped and refused orders to return, could be a threat, so he waits for a second recruit to arrive. Once he does, the pair meet the driver and his two passengers, who have mental health conditions that prevent them from communicating. Relying only on the driver’s word, the recruits learn that he’s a care worker and had driven his clients to the grocery store. On the way back, the driver says, the front-seat passenger had lunged at the steering wheel. (Text by Mikey Galo/News21)

What went wrong

The recruits initially mistake a mental health crisis for a drunken driving incident. There are reasons for the misunderstanding – the driver is excited and refuses to get back in the car. Once they greet the sedan’s passengers, they start to assess what’s really happening.

What went right

Before the recruit in the lead car leaves his vehicle, the sedan’s driver jumps out – holding a black object in his left hand. He waves his arms and shouts at the recruit, who gets out of his car but doesn’t understand what the driver is saying. The recruit stays behind the open patrol car door. He can see there are other people in the sedan, but his eyes watch the driver’s left hand.

“Stop. Stop and get back in your vehicle.”

The driver shouts more and takes three steps forward. The recruit rests his right hand on his holstered service pistol.

“Stop where you are and get back in your vehicle,” the recruit says, his voice louder now.

The driver takes another step forward, then stops and lowers his arms to his sides. It’s evident that the object in his left hand is a phone.

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry. I just need help over here.”

The driver walks back to the sedan. The recruit removes his hand from his gun, which remains holstered.

The recruits, with patience, calm the driver and his passengers. Twenty minutes after the traffic stop, they leave for home.

Paul Goodrich, a recruit with the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department, addresses field training officer Andrew Lamle during an exercise called Unknown Traffic Stop on Friday, July 8, 2022, while field training officer Joseph Dransfield looks on. It simulates real-life scenarios officers often encounter in the field. (Text and photo by Mikey Galo/News21)

DeAndra Yates, a gun violence activist who now works for the Indianapolis police department’s Non-Fatal Shootings, Advocacy and Support Program, said all the recent reforms started with the public.

“The community is being impacted, right? So why not allow them to have a seat at the table and a voice in that space?” Yates said.

The Rev. David Greene, senior pastor of Purpose of Life Ministries Church, also credited community activism for the creation of the police department’s civilian-led use-of-force board and a mental health team that accompanies officers to calls during the work week.

The actions help the community and officers, Greene said.

“Those things didn’t exist until recent years,” he said. “And it’s because the community said, ‘Hey, we need changes in this area.’”

Left: DeAndra Yates works for the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department’s Non-Fatal Shootings, Advocacy and Support Program. The gun violence advocate says all the recent police reforms in the department have started with public outcry. (Photo by Reagan Creamer/News21) Right: The Rev. David Greene preaches at the Purpose of Life Ministries in Indianapolis on Sunday, July 10, 2022. Greene is the leader of Concerned Clergy of Indianapolis and an advocate for police reform. (Photo by Mikey Galo/News21)

Top: DeAndra Yates works for the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department’s Non-Fatal Shootings, Advocacy and Support Program. The gun violence advocate says all the recent police reforms in the department have started with public outcry. (Photo by Reagan Creamer/News21) Bottom: The Rev. David Greene preaches at the Purpose of Life Ministries in Indianapolis on Sunday, July 10, 2022. Greene is the leader of Concerned Clergy of Indianapolis and an advocate for police reform. (Photo by Mikey Galo/News21)

Approaches to training

Indianapolis police incorporate de-escalation training from the Police Executive Research Forum, an organization focused on best practices in policing.

Its program, known by its acronym, ICAT, emphasizes that use-of-force training needs to move beyond just being taught in police academies to integration into ongoing training for veteran officers.

Tom Wilson, director of the forum’s Center for Management and Technical Assistance, said the program emphasizes a continuous, holistic approach when teaching officers how to reason through situations and communicate with the people they encounter.

“Over the course of the last few years, law enforcement leaders have recognized, ‘Hey, this is important stuff,’” Wilson said. “And this is really stuff that we’ve been talking about in policing for years. It’s just getting back to some really good, common sense policing.”

As of 2021, Wilson said, about 700 departments had received at least parts of ICAT training.

How many training hours a department receives, through different methods and programs, varies widely. The San Antonio Police Department provided 80 hours of de-escalation training in 2018, according to self-reported data in the census of police training academies. The Philadelphia Police Department reported five hours. The Georgia patrol had the lowest reported, at one hour.

In addition, competing approaches to de-escalation training complicate the landscape and make it difficult to determine what methods are effective.

“We don’t know how that particular training impacts a wide array of agencies across different communities, different socio-economic statuses, population sizes and things like that,” said Morgan Steele, a national research coordinator for the National De-Escalation Training Center in Detroit.

Still, researchers have started making some analyses. In a study earlier this year, Engel, the University of Cincinnati researcher, wrote that data from the Louisville Metro Police Department in Kentucky showed significant reductions after the ICAT de-escalation training – 28% in use-of-force incidents, 26% fewer “citizen injuries,” 36% fewer officers injuries.

Departments “should continue to implement and evaluate de-escalation trainings and adopt other resiliency-based approaches to police training,” the study says. “To facilitate long-term changes in police behavior, a holistic approach is recommended that supports training tenets with complementary policies, supervisory oversight, managerial support, and community involvement in reform efforts.”

In a 2020 study on police reforms, Engel wrote that departments have been slow to incorporate de-escalation training, as newer models run counter to more traditional methods that encourage quick decision-making and bring up department fears that de-escalation puts officers in greater danger.

“Concerns regarding officer safety run deep within police organizational cultures,” Engel’s study says, “and some trainers have resorted to avoiding the use of the word de-escalation altogether in training sessions, rather describing these techniques as opportunities to defuse situations.”

But some acknowledge that reform can’t depend on research.

“Policing can’t wait,” said William Terrill, who served on President Barack Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. “It can’t wait, right? You can’t wait for 10 years of research and say, ‘Well, we’re going to hold up and wait until the final evidence is in 10 years from now.’”

Terrill, who holds a doctorate in criminal justice, said police often escalate situations that otherwise were benign. He recently analyzed more than 500 videos from body cameras worn by officers in two Texas police departments.

“About 1 out of every 5 times – 21% of the time – officers took a completely compliant situation where the suspect is complying with everything, and the officers actually escalated it through their behavior,” he said. “They used force on a compliant suspect.”

Terrill said it’s also about changing the culture of how police serve the public every day. When department leaders reviewed his finding that their organizational culture encouraged traffic stops, pat downs and searches, they called that “good policing,” he said.

“You’re getting a situation where you’re creating, from a community perspective, what is low level but still force,” Terrill said. “Cause we’re not talking about deadly force, right? But, from a scientist’s perspective, I worry about the legitimacy and the cumulative effect that has on a particular community that’s constantly getting stopped, searched, patted down and, you know, only having something found 1 out of 10 times.”

Indianapolis police de-escalation training scenario: felon and drugs

Three recruits stop a black Chevrolet with three occupants. One approaches on the driver's side while the others approach the passenger side in single file. Once the recruits introduce themselves and run background checks, they learn that a passenger has a warrant for his arrest. When the lead recruit pulls the wanted man from the car, he sees the suspect was sitting on a bag of cocaine, a bag of marijuana and a fake driver’s license. The recruit alerts the others, and all three passengers are removed from the car so it can be searched. (Text by Mikey Galo/News21)

What went wrong

Miscommunication. This is the lead recruit’s first traffic stop. He forgets that as the primary officer, he’s supposed to direct the other two recruits. That lack of communication could mean a stop going wrong and escalating into something bad.

“Where do you want me?” one asks the lead.

“Um, I think on the other side.”

“Ready over here,” the third recruit says.

The lead recruit stops. He has already introduced himself to the car’s driver, but he loses his place. His training officer steps in, but not before he lets the recruit struggle for a few seconds.

“This is your show,” he says. “You’re the primary officer. You’re directing this.”

The recruit nods.

“OK,” the recruit says. “OK, there are three people in the car. You’re over here. Let’s try again.”

What went right

Clear communication in other ways. When a recruit pulls the wanted man from the car, drugs are visible. The recruit handcuffs him.

“Before you move, do you see anything?” his training officer asks him.

“Yes.”

“OK, so make that known,” the trainer advises. “The people in the car know that’s there. But you need to relay that to your beat partners because we don’t know what your beat partners can see. Your beat partner behind you is definitely not going to be able to see. So just say, ‘Hey, there’s dope in the front seat. Make sure they don’t grab it.’ And then go about your business.”

“Do you see the dope in the front seat?” he asks the recruit on the driver’s side.

“Yes.”

“Do you see the dope?” he asks the recruit behind him.

“No,” she responds.

“It’s right here in front of me. Make sure nobody moves it.”

“Got it.”

The recruit then walks the suspect to the back of the Chevrolet.

The chilling effect of police violence

Even hard-won reforms don’t provide a guarantee. Greene, the Indianapolis pastor, said more can be done.

He pointed to the recent death of Herman Whitfield III, 39, of Indianapolis, who died in the custody of police who had been called to his parents’ home for a mental health crisis. Police Tased and restrained Whitfield before he died in April, according to media accounts.

“That escalated a situation that could have been easily, in my opinion, de-escalated,” Greene said.

The autopsy report released by the Marion County Coroner’s Office listed Whitfield’s cause of death as “cardiopulmonary arrest in the setting of law enforcement subdual, prone restraint, and conducted electrical weapon use.” Morbid obesity and hypertensive cardiovascular disease were listed as contributing conditions.

Indianapolis police say a criminal investigation into Whitfield’s death is ongoing.

Greene said officers escalated the situation, which may make people hesitant to call the police for help in an emergency.

“Do you think that those parents are going to call 911 next time and say, ‘OK, police, I need you?’ They’re less likely to do that. People who are familiar with their situation are less likely to do that because of what happened to a young man who was completely naked.”

Activists also are concerned about a new Indiana law that requires a statewide review board to establish new standards for training, including in de-escalation. Activists fear that will mean fewer hours for officer training.

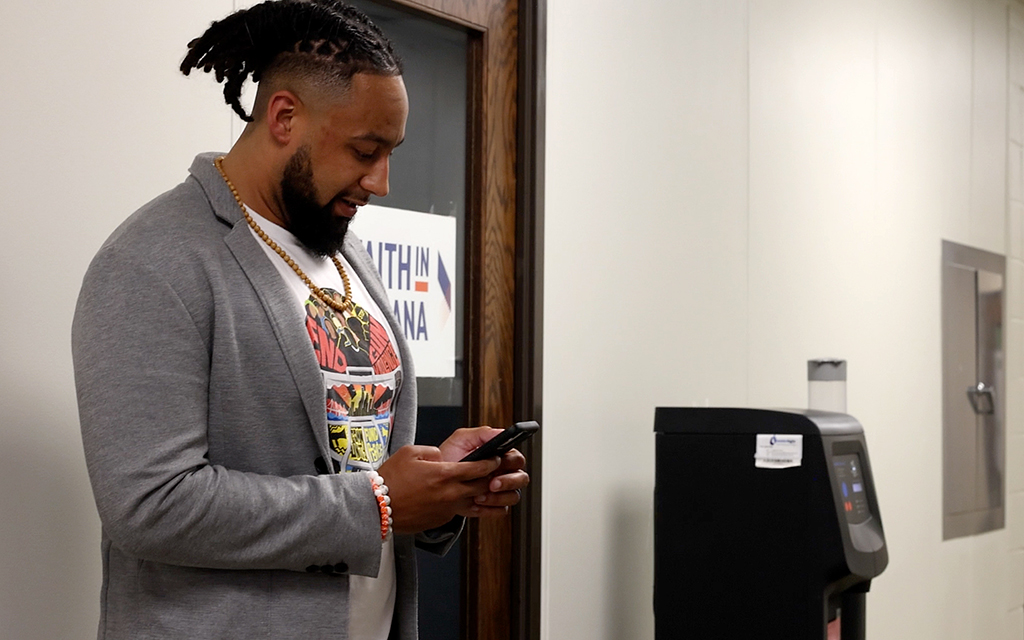

Josh Riddick checks his phone outside the Faith in Indiana office Indianapolis. He fears a new law empowering a statewide review board to establish training standards will mean fewer training hours on such subjects as de-escalation. (Photo by Reagan Creamer/News21)

Josh Riddick, an organizer with the civil rights organization Faith in Indiana, expressed his frustration.

Legislators, he said, “didn’t take into account the work the largest police force in the state has done … to make sure it is doing right by the community. So again, that inability to listen and consider such a large population base, such a large law enforcement group, is frustrating.”

Cummings, the deputy chief of training, said it’s “purely speculative” to say the law will lead to fewer training hours.

What comes next?

The future for de-escalation training in police departments is mixed.

Angela Harrelson, George Floyd’s aunt, said the key is officers who are embedded in a community.

“When you know your community, you can de-escalate a situation better than someone that doesn’t,” Harrelson said. “They can say, ‘Oh, there’s so-and-so there,’ you know, ‘I know him. I know his parents, let me talk to him.’”

Greene said the key is trust in a partnership of police and the public.

“I don’t think either side wins without the other,” Greene said. “And I want to be clear about that. The police department will not win without the community, and the community is not going to win without the police department. We have to have that bridge.”

Terrill said there’s hope.

“My experience over many years is that most agencies want to get better,” he said. “They want to do good. They just disagree about what good is sometimes, or what the proper pathway for that is. But they’re open to it.”

News21 reporter Piper Vaughn contributed to this article. Mikey Galo is Inasmuch Foundation Fellow. Reagan Creamer is Hearst Foundation Fellow.