(Video produced by Jessica Alvarado Gamez/News21)

Pain, action and hope: Activists have battled for police reform for decades

OAKLAND, Calif. – For years, Cephus Johnson was Uncle Bobby to only a few folks, including his nephew, Oscar Grant III. Thirteen years later, Johnson points to a coin-sized gouge in the platform at the BART transit station in Oakland, saying it’s from the bullet that a transit police officer in 2009 fired into Grant’s back, killing him.

Grant’s death fueled Johnson’s new life: The retired postal worker is committed to changing policing in Oakland and, perhaps, America. Johnson and his sister, Grant’s mother, have built a foundation and a campaign to support families affected by police death

“This pain, we have tried to turn into some form of purpose,” Johnson said.

Police reform activists often are friends and family members directly marked by tragedy, including the aunt of Breonna Taylor, who was killed during a no-knock warrant in Kentucky and Marion Gray-Hopkins, whose son was shot by police three decades ago in Maryland. Other activists are community members or leaders who work outside the government institutions that set policies, laws and practices.

(Audio by Arrthy Thayaparan/News21)

Some work inside the system, such as the state lawmakers who changed police surveillance laws in Maryland, a Phoenix council member who started a civilian oversight office, and a police chief in Georgia whose department offers motorists auto-repair coupons instead of traffic tickets for equipment failures.

Activists and their supporters – elected officials, police and community members – say the elements of police-reform activism often take years of commitment, concerted collaboration and struggle. The journey is marked by the lessons, mistakes, debates and pushback of previous generations.

Colin Wayne Leach, a professor of psychology and Africana studies at Columbia University’s Barnard College, called activism a wide net, with disparate groups pushing for change simultaneously.

“When we think about social movements and change in society, it’s happening on many different levels at once,” Leach said. “And usually, most of us are only paying attention to the most obvious one, or the one that’s in the media, or the one we’re familiar with. It’s all happening at once, and it’s having different effects.”

“That moment (of change) is the product of all those different things happening, at all those different levels, at the same time.”

Elaine Brown, 79, is a former leader of the Black Panther Party, which was founded in Oakland, California, more than five decades ago. Brown says the party’s goal was to educate and liberate. (Photo by Diannie Chavez/News21)

The catalysts: Oakland

The only thing small about Elaine Brown is her frame. She’s a former top leader of the Black Panther Party, a community-forward, anti-police-brutality organization founded in Oakland more than five decades ago. Iconic images of rifle-toting men and women in black berets, fists raised in the Black power salute, lifted Black pride and challenged mainstream society’s comforts, even as the organization provided free breakfasts in Black neighborhoods while fighting police misconduct in ways that drew accolades and controversy.

Although the party became known for its deadly encounters with police, Brown said Panther leaders knew they couldn’t win a battle with police.

The “goal was to educate and liberate,” she said. “We’re not going to take on the police. We’re not that stupid. We had our little guns. We could not have sustained a fight with” Oakland police and other law enforcement. “We could never possibly challenge the police.”

But the party mattered then and still matters now, said Brown, who joined in her mid-20s and remembers sleeping on the floor, with no time for a personal life.

“All of us will tell you that the greatest part of our lives, the greatest thing we ever did, was to be in the Black Panther Party,” she said. “No matter how hard it was.”

The party provided a model for generations to follow, said Brown, 79, who calls out some younger activists for not knowing the meaning of sacrifice.

“I ask the young people today, ‘What are you doing? What are you sacrificing? Are you giving up something?’

“This is my example: ‘I go to the Black Lives Matter rally and I say defund the police, Black Lives Matter, then I go home and eat a vegan sandwich and feel like I’m some kind of an activist.’

“Are you kidding me?”

Brown said reform means being willing to risk your job, to consistently confront the uncomfortable.

“I think the success of the Black Panther Party in forms of community policing or policing itself was that we certainly gave Black people a model for courage,” she said.

Brown, who’s now working on a $72 million affordable housing project, said the faces of police administrations and officers have changed over the past half-century, but not nearly enough has changed in Oakland.

The Oakland Police Department, under federal oversight for 20 years after an investigation showed a group of Oakland officers going by the name “The Riders” allegedly falsified reports, planted evidence and beat up people, according to court documents.

In September, a federal district court judge ended the oversight but placed the department on a year’s probation, according to media reports.

Brown remains skeptical.

Oakland Police Chief LeRonne Armstrong is photographed in his childhood neighborhood in West Oakland on June 28, 2022. Nearby, several of his officers stand guard. (Photo by Diannie Chavez/News21)

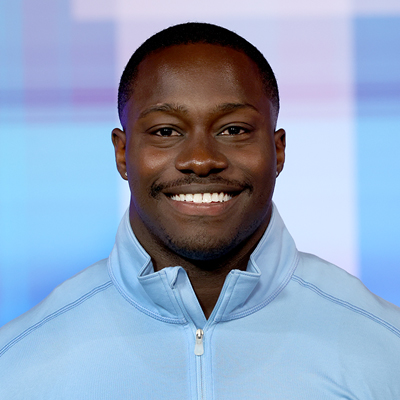

LeRonne Armstrong, who was named chief in 2021, understands that skepticism. Armstrong, 49, grew up in a West Oakland neighborhood where he didn’t feel safe in his own bed at night. When he was 13, he lost his 16-year-old brother to gun violence.

On a hot summer day years later, Armstrong brought a phalanx of media, police and city staff to a park in his old neighborhood. Two boys dribbling a basketball on a concrete court stopped as a blacked-out SUV and sedan pulled up to the park entrance, then left the court.

The chief, a 22-year veteran,was there to talk about why he’s policing a city where police aren’t always trusted.

“Growing up here, when your community hears you join the police department, everybody is going to say, ‘What? Why?” said Armstrong, who was named police chief in 2021, several months after George Floyd died.

“You almost feel like you’re not going to be accepted anymore. And that’s how big of a deal it was for me. It was scary. It was intimidating. It was very sobering that I was here, but also a sense of belonging because I knew how much I felt like my community needed that representation.”

Black representation at the top of police ranks is meager. About 8.5% of police chiefs in the U.S. are Black or African American, according to Zippia, a jobs data site.

Although he’s a rarity in the ranks, Armstrong shares most police chiefs’ dismay at demands to “defund” the police. Officers aren’t able to respond as quickly to calls as he would like, and departments need more money to hire officers.

“If you were to talk to the vast majority of people in this city,” Armstrong said, “they would tell you that the city does not need less police. But they feel that way because they want better policing. They want fair and just policing. They want police officers that don’t violate their rights. They want police officers that do their job the right way.”

Growing up in West Oakland – an area Armstrong characterized as the most dangerous neighborhood in California – means he makes safety a priority, the chief said.

Left: Cephus “Uncle Bobby” Johnson places his hand next to a gouge on the floor of the Fruitvale BART station on June 27, 2022, in Oakland, California. Johnson believes it’s the “exact spot” his nephew, Oscar Grant, was shot and killed by a BART officer in 2009. Right: Cephus “Uncle Bobby” Johnson is photographed outside the Fruitvale BART station on June 27, 2022, in Oakland, California. The mural of his nephew, Oscar Grant II, was created by Oakland artist Senay “Refa One” Alkebulan and unveiled in 2019. (Photos by Diannie Chavez/News21)

Top: Cephus “Uncle Bobby” Johnson places his hand next to a gouge on the floor of the Fruitvale BART station on June 27, 2022, in Oakland, California. Johnson believes it’s the “exact spot” his nephew, Oscar Grant, was shot and killed by a BART officer in 2009. Bottom: Cephus “Uncle Bobby” Johnson is photographed outside the Fruitvale BART station on June 27, 2022, in Oakland, California. The mural of his nephew, Oscar Grant II, was created by Oakland artist Senay “Refa One” Alkebulan and unveiled in 2019. (Photos by Diannie Chavez/News21)

At a BART station miles from West Oakland, Cephus Johnson reflects on his journey from the military to a career in engineering to the Postal Service to police-reform activist after the death of his 22-year-old nephew on New Year’s Day 2009. He speaks in front of a mural at Fruitvale station dedicated to the life of Oscar Grant III, not far from that coin-sized gouge in the platform.

Officer Johannes Mehserle was one of the Bay Area Rapid Transit officers who responded to reports of a fight at the Fruitvale station that day. He shot and killed Grant as he lay on his stomach, handcuffed. Mehserle, who said he accidentally fired his weapon instead of his Taser, was convicted of involuntary manslaughter and sentenced to 11 months in jail.

Johnson said the protests that erupted in Oakland after Grant’s death have fallen quiet, but the mission and the movement remain. His family believes his nephew’s death – one of many among young Black men and women each year – was a catalyst for the Black Lives Matter movement.

Johnson and his sister started the Oscar Grant Foundation in 2010. At first, he struggled in the role.

“I didn’t know how to talk to folks,” he said. “I wasn’t no public speaker, not on no level that it turned out to be. I had to say something because my sister Wanda’s voice was gone. She was mute. She could not say nothing because she was so brokenhearted.”

The foundation provides grief sessions, scholarships, tutoring and athletic programs to predominantly Black communities.

Johnson later turned the operation of the foundation over to his sister and created the Love Not Blood Campaign to end police violence. The campaign supported legislation, such as a law that allows the public access to records related to any law enforcement officer under investigation for firing a gun, use of nonlethal force, sexual assault or dishonesty.

Activism often ebbs and flows. By 1982, the original Black Panther Party had been dismantled.

But activists continue the work, sometimes on the streets, sometimes in city hall, other times at the state capitol.

Marion Gray-Hopkins visits the resting place of her son, Gary Hopkins Jr,. at the Fort Lincoln Funeral Home & Cemetery in Brentwood, Maryland. The 19-year-old was shot and killed by a police officer in 1999. (Photo by Diannie Chavez/News21)

The lawmakers: Baltimore

Sixteen days after he lost his father to bone cancer in November 1999, Gary Hopkins Jr., 19, went to a community center dance dressed in his father’s “dad slacks” and lizard skin shoes.

Hours later, his mother picked up the phone. “They shot Gary!” her son’s friend screamed.

Over the years, the scent of her husband and son has faded from the clothes Hopkins wore that night. But Marion Gray-Hopkins, 66, remembers driving to the scene and seeing her son on the ground, from a distance. She remembers asking to hold her son and being told no, his body was evidence. There was no video, no social media in 1999.

Marion Gray-Hopkins, at her home in Maryland, shows a photo of her son, Gary Hopkins Jr., who was shot and killed by a police officer in 1999. (Photo by Diannie Chavez/News21)

She also remembers that nothing happened to the off-duty officer who shot her son, who claimed Hopkins lunged for another officer’s gun during a dispute.

Gray-Hopkins is the co-founder and executive director of the Coalition of Concerned Mothers, which provides a space for mothers who are affected by gun violence to grieve and work on reform strategies, such as repealing Maryland’so-called Officer’s Bill of Rights.

“We’re in a sorority we didn’t pledge to be a part of,” Gray-Hopkins said.

Activists are working to change laws, fight in the courts and, in some cases, get elected to office to reform policing. Sometimes, after years of trying, they drive change on their terms, he said.

Most recently, Baltimore successfully challenged police surveillance law. Maryland also was the first state to repeal its so-called law enforcement bill of rights. Elected officials said the repeal and other legal changes were accomplished through a series of incremental changes, working with Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle and other community organizations.

Maryland state Sen. Jill Carter, a Democrat, was among lawmakers who proposed to repeal or alter the bill of rights in 2014. Their proposals were rejected, she said.

In April 2015, Freddie Gray died after he was arrested and transported to jail in a Baltimore police van. In response, Maryland passed no major police reforms.

Maryland state Sen. Jill Carter speaks to Assistant State’s Attorney Dalya Attar at a voting site on July 12, 2022, in Baltimore. Carter, a Democrat, helped drive new laws aimed at reforming police practices. (Photo by Diannie Chavez/News21)

“You can’t really fire a cop in Maryland because they have the system so sewn up, they are not afraid of getting fired,” said Lawrence Grandpre, research director at Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, which focuses on improving the lives of Black people and police accountability.

But Carter said a slew of state reforms after Floyd’s death in May 2020 required public disclosure of police discipline records and created criminal penalties for officer misconduct involving use of force.

Sometimes, activists take their cause to court. Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle in 2021won a lawsuit against the Baltimore Police Department that claimed police aerial surveillance technology violated the First and Fourth Amendment rights of the public. That technology no longer is used.

“This spy plane is just one example of how technocratic, nondemocratic, nonaccountable flows of money are being injected into your city in the name of protecting you,” said Grandpre, who got involved in police reform after the 2012 death of Christopher Brown at the hands of Maryland police.

Sometimes, activists take government roles.

Carlos Garcia campaigned on a platform of police reform when he was elected to the Phoenix City Council in 2019. He initiated the creation of the Office of Accountability and Transparency, a police oversight board. (Photo by Piper Vaughn/News21)

Carlos Garcia, 39, a Phoenix community organizer turned City Council member, wears his activism as a fashion statement. He often wears T-shirts with such political messages as “Water is Life,” and “End Police Brutality” – the shirt he wore at a 2020 council meeting.

“I carry my heart on my sleeve and my message on my chest,” said Garcia, who represents District 8 in south Phoenix. “It’s to show who I am.”

On the ground, he said “organizing and activism and having a political position work hand-in-hand. There’s not one more effective than the other.”

But Garcia, who was elected in 2019 on a platform of police reform, said he now has “more power to make change.”

One major change he spearheaded was the 2021 creation of the Phoenix Office of Accountability and Transparency, a controversial police oversight board that was to be led by civilians.

But the Arizona Legislature rolled back its power, requiring law enforcement officials to make up two-thirds of the board and mandating that half the members approve investigations into alleged police misconduct.

Garcia acknowledged the blow struck by the Legislature.

“What I’m proud of,” he said, “is that my colleagues and those of us who are working to make this office happen are continuing to work to implement the initial intentions of the office.”

Gray-Hopkins, the grieving mother turned activist, said change is grueling, marked by crisis after crisis.

“As we continue to grow that power of the people, they’re not going to have any option but to make the changes that are demanded,” she said of police. “But it’s just that change is slow. Change is very small.”

Glow sticks hang in a tree at a memorial for Jayland Walker in Akron, Ohio, on July 8, 2022. Walker died after being shot 46 times by Akron police officers on June 27. (Photo by Gabriela Tumani/News21)

The crisis: Akron, Ohio

June 27, 2022.

One 25-year-old Black man, eight police officers.

Sixty shots fired, 46 struck their target.

Jayland Walker becomes another of the hundreds of people killed by police so far this year.

National attention, a public outcry, protests and a police investigation follow.

Breonna Taylor’s aunt, Bianca Austin, and other activists arrive in Akron to protest police abuse and support Walker’s family.

“We can first start with accountability,” Austin said. “We can first start with police humanizing the citizens who they are supposed to serve and protect.”

The father of Jacob Blake Jr. – who is paralyzed after police in Kenosha, Wisconsin, shot him in the back in August 2020, also came to Akron.

“I feel like it’s our duty to stand up for the families,” said Jacob Blake Sr., whose organization, Families United, travels from city to city to support families victimized by police brutality.

There were 1,055 fatal police shootings in 2021, according to data from Statista, and 730 as of early September 2022.

In Akron, people are weary but willing to go on.

“The death of Jayland Walker has brought the people together,” said the Rev. Raymond Greene Jr., 46, the executive director of Freedom Bloc, which develops Black leadership.

“We’re going to continue to be out here for Jayland Walker and stand in solidarity with the family,” Austin said. “We’re going to continue to organize and be out in the street because we don’t fear the police.”

LaGrange, Georgia, police officers Jim Davidson, left, and Braxton Willis demonstrate the use of a BolaWrap restraint device on July 15, 2022. The BolaWrap, which gives officers a less-lethal tool to employ, is part of several reforms at the police department. (Photo by Donovan England/News21)

The police leader: LaGrange, Georgia

On a humid, hot summer day, Officer Jim Davison teaches two police recruits how to use what he calls “less lethal force.” A test dummy is upright, in front of the recruits. An officer releases a BolaWrap. Two wires snap around the dummy, trussing arms and legs to the body.

After the training ends, Davison asks the recruits whether they’d like to use the BolaWrap on each other to show that it’s less painful than a Taser. It’s one more way that Police Chief Louis Dekmar has innovated police reforms by teaching officers and recruits to shoot to incapacitate, rather than to kill, if the altercation isn’t life-threatening.

Dekmar is among police leaders from across the country, from Oakland to Denver to Indianapolis to Oregon, who are driving change from the top down.

Reform minded police chiefs are gaining attention. A job description for police chief in Buffalo Grove, Illinois, population 43,000, required that candidates be “familiar with progressive policing principles.”

LaGrange Police Chief Louis Dekmar has led several reforms in this Georgia city of 32,000. “We’re enforcing the law. We’re just enforcing it in a way that doesn’t do more harm,” says Dekmar, who’s been chief for 27 years. Photo taken July 15, 2022, in LaGrange, Georgia. (Photo by Donovan England/News21)

Officials in Phoenix, the nation’s fifth largest city, this year hired Michael Sullivan, who has reform experience in Baltimore, to serve as interim chief of a police department that’s under a federal civil rights investigation.

Dekmar, in his 27 years as chief in LaGrange, population 32,000, has instituted a series of innovations: requiring body cameras 13 years ago when few departments provided the technology; issuing repair coupons instead of traffic tickets for automotive equipment failures; requiring four times more officer training than the state minimum; and providing civil rights training so his officers understand the historically fraught nature of policing.

Dekmar said that in LaGrange, he has an opportunity to not only solve crimes but build the trust to prevent them.

“We’re enforcing the law. We’re just enforcing it in a way that doesn’t do more harm,” he said. “It’s almost like the police need a Hippocratic oath.”

He acknowledges some advantages – he has nearly three decades as chief, and LaGrange is large enough to provide resources but small enough to be familiar with.

Ernest Ward, a community activist and former LaGrange police officer, sits on a park bench at Lafayette Square. He said the city is moving away from the traditional model of policing.

“You go out, arrest people, bring them in,” Ward said, describing his seven years on the force. “It was almost like a gap that exists between law enforcement and the community.”

Ward said Dekmar is trying to bridge that gap.

“I believe he’s implemented a lot of things within the community that a chief of police probably shouldn’t be involved in,” he said. “Right now in our community, we have elementary schools that are racially identifiable. We have certain elementary schools, they’re either majority all white, and you go to other schools and they’re majority all Black.”

Left: The Callaway Memorial Tower in LaGrange, Georgia, on July 16, 2022. Police reforms in this city of 32,000 began years ago with the installation of body-worn cameras. Right: Former police officer Ernest Ward shares some of the history and culture of LaGrange, Georgia, on July 14, 2022. He says the city is moving away from the traditional model of policing. (Photos by Donovan England/New21)

Top: The Callaway Memorial Tower in LaGrange, Georgia, on July 16, 2022. Police reforms in this city of 32,000 began years ago with the installation of body-worn cameras. Bottom: Former police officer Ernest Ward shares some of the history and culture of LaGrange, Georgia, on July 14, 2022. He says the city is moving away from the traditional model of policing. (Photos by Donovan England/New21)

Dekmar acknowledges he has more work to diversify his force of 97 sworn officers. LaGrange is a majority-minority city – 51% Black, 41% white, with 8% Latino or Asian, according to the census, Dekmar, who’s white, leads a department in which 80% of officers are white.

Dekmar said his philosophy has led to a drop in arrests and a rise in community trust. According to the department’s annual report, LaGrange police made about 2,800 arrests in 2021, compared with an average of 6,000 a year during the 1990s.

“I would call myself someone that looks at the evidence, listens to my community and makes adjustments so that we’re providing the best service we can,” said Dekmar, an Air Force veteran who worked in Wyoming and other Georgia police departments before coming to LaGrange.

One of his innovations comes from elsewhere – he saw that Oregon helped motorists who couldn’t afford minor car repairs.

“So now, on top of getting that headlight fixed, I got a $150 ticket,” Dekmar said. “Does that help them? I don’t think so.”

The department developed partnerships with car repair businesses. Instead of writing tickets, they hand out coupons with discounts to get the repairs fixed within 30 days. Drivers stopped again for the infraction are cited.

Other initiatives were developed by or with community leaders, Dekmar said.

“Just a host of initiatives that were predominantly identified by the police department or facilitated by the police department, but very quickly coalesced with partners so that the community was engaged in helping address these issues,” he said.

In 2009, Dekmar required all officers to wear body cameras and mandated that every contact – patrol officers, gang squad, illegal drug investigators – had to be recorded.

“Everyone involved in enforcement should have video,” he said. “ If you’re ashamed to video your practices, then you might want to re-examine your practices.”

Reform starts with training. Recruits undergo two to three weeks of training by LaGrange officers before they’re sent to the police academy, Dekmar said. On return, they receive an additional four to five weeks of scenario-based classroom training with the department. Recruits then transition into a 12- to 15-week field training program along with comprehensive written tests and scenarios.

After training is complete, Dekmar quizzes them on how to handle different scenarios. He said that 90% will do well, and the rest will be sent back for additional training.

“The state requires 20 hours a year of continual training, which is woefully inadequate,” Dekmar said. “We require our officers to have a minimum of 80 hours.”

Recruits also learn the history of civil rights in LaGrange and the U.S. focusing on police treatment of communities.

“If you don’t know your history and know your past, you’re going to repeat it,” said Officer Bryant Mosley, a licensed counselor who works part-time as a LaGrange police officer with an emphasis on mental-health crisis work. “You have to stay in the forefront with everything.”

Dekmar said putting policing into context makes sense.

“It’s riot. Unsettled calmness. Tension until the next episode,” he said. “It’s like we don’t look at what’s happened in the last 50 years and say, ‘Well, maybe we need to do something different.’”

One route was shifting to a policy in April 2021 of shooting to incapacitate rather than kill, based on data Dekmar reviewed on 5,000 police shootings.

Strengthening the relationship between LaGrange police and residents is an ongoing process. The community that’s most in need in LaGrange has the least amount of trust in police, Ward said.

“I wish that law enforcement would know and understand that nothing is going to change without intentionality,” he said. “I wish that the citizens would understand that nothing is going to happen overnight.”

Others in the LaGrange wish Dekmar would insert himself in all aspects and levels of the city.

Alonzo Roberts, a former gang member turned community activist, is one of those pushing for police reforms.

Although Dekmar is available to the community, he said, people in need have to make the effort to go to him.

“Get the community involved,” Roberts said. “Make the community feel like they’re involved, and you’ll have a better police department.”

Oakland Police Chief LeRonne Armstrong, left, watches a basketball practice inside his former high school, McClymonds High School, in Oakland, California. In his earlier days, Armstrong used to play basketball on a regular basis. (Photo by Diannie Chavez/News21)

The innovators: Oakland

Activists cite common sense, creativity, understanding and patience as the key to reform, for police and the public. Change, with activism, is inevitable, they say.

“The uniform is not who I am,” said Armstrong, the Oakland police chief. “At the beginning of the day, when I wake up in the morning, I’m an African American man from Oakland. When I take the uniform off at night, I’m still that same African American man from Oakland. And when I wear this uniform with honor and with pride, I’m that same African American man that just cares about his community, whether I’m in uniform or not.”

Leach, the professor at Barnard, said it’s profound that members of the public now think it’s a legitimate political question to ask what the police budget is.

“There are so many things that have changed on a small scale,” he said. “There are so many things that are now on the table that people are informed about.”

Brown, the longtime Black Panther, recalls a conversation she had with a young Black man in prison who told her “the pendulum will swing our way again.”

“I do believe that it is in the nature of things, of the yin and yang of things, of the black and white and the action and reaction and all of those things that seem to be a part of the very foundations of the nature of things on this planet, that the social pendulum will swing back our way,” Brown said. “And those of us who are in the business of creating a humane and egalitarian society will have a platform to build on.

“And that gives me hope.”

News21 reporter Arrthy Thayaparan contributed to this article. Ben Porter is a Buffett Foundation Fellow.