Washington state rolls back some of the sweeping police reforms passed in 2021

Sept. 30, 2022

SEATTLE – Roger Goodman called the summer of 2020 apocalyptic.

The economy had cratered. COVID-19 ran rampant. Forest fires choked the West.

“Everything wrong was happening at the same time,” the Washington state lawmaker said.

Then came a flashpoint: The deaths of Breonna Taylor in Kentucky and George Floyd in Minnesota pushed protesters across the country into the streets, demanding justice and police reforms. Major protests in Seattle continued for weeks.

Goodman knew the Legislature needed to take action on police reform, so he got to work.

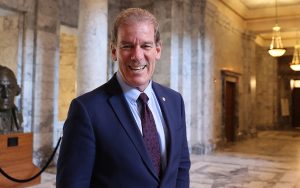

“I put out the call, and we sat down at the table,” said Goodman, Democrat who represents Kirkland, a suburb east of Seattle. “It took about eight or nine months during the course of 2020 to prepare for the 2021 legislative session.”

Goodman put together a leadership team that included community members, lawmakers, and police he called passionate about police reform. They met with advocates, families who have lost loved ones, police unions, law enforcement officials and leading scholars. They introduced a dozen bills.

The legislation prohibited the use of chokeholds and other types of neck restraints, banned no-knock warrants, restricted the ability to shoot at moving vehicles and banned “the use of all sorts of military equipment, weapons, heavy caliber weapons and tanklike vehicles,” among other major changes, Goodman said.

Washington state Rep. Roger Goodman, D-Kirkland, says it took about eight or nine months of 2020 to prepare for the 2021 legislative session, which produced limitations on use of force and other police reforms. (Photo by Olivia Jennings/News21)

Gov. Jay Inslee, a Democrat, signed the sweeping package of reforms, earning Washington national headlines as a state making quick, comprehensive action.

But the legislation had critics, including Republican lawmakers, and the state’s law enforcement community wasn’t completely on board, either. Activist groups wanted to see how the reforms would play out.

Now, more than a year later, the state has rolled back – supporters would say repaired – some of its measures.

Republican Rep. Chris Corry described the initial legislation as one-sided, unclear and inflexible. He said the Legislature needed to fine tune the initial laws, which weren’t “really fleshed out.”

“Typically, a lot of times, we’ll see bills will take much longer to adjust and develop because we’re trying to get it right the first time,” Corry said. “In this case, there was some stuff that was added in that turned out to be a really big detriment to our communities. It was actually hurting police response to individuals in crisis.”

Corry, who lives in Yakima, southeast of Seattle, said he and his Republican colleagues signed on to what he called repair bills so they “could correct that for our police officers.”

Spokane Police Chief Craig Meidl said he knew the 2021 legislation would hinder police work. He joined 17 other chiefs and sheriffs from across eastern Washington to express their concerns at a news conference.

“The intent of the press conference is to say, ‘Hey, this is coming, here’s what we will no longer be able to do, here’s what we can do because of the laws, and these are things that we now have to do.’”

For example, officers said the 2021 legislation prevented them from using force to stop people from fleeing “temporary investigative detention,” known as a Terry stop. The legislation passed this year makes clear that police can use force – with reasonable care – in Terry stops.

After Washington enacted police reform laws in 2021, Spokane Police Chief Chief Craig Meidl wanted the public to understand policing would “look different because these laws now say there are certain things we can’t do and or certain things we must do.” (Photo by Olivia Jennings/News21)

Jim Ritter, a retired Seattle police officer who runs the Seattle Metropolitan Police Museum, said police were an afterthought in the 2021 legislative process.

“A lot of times when decisions are made, they don’t include the people that are doing the work because they think they know how to solve the problem without doing the job,” said Ritter, who was in law enforcement for more than 40 years. “It’s like me explaining to a dentist how to clean my teeth. I know and I have no right to be imposing rules on his profession that I know nothing about.

“But there’s a certain arrogance in politics where you have people that are reacting. I think you have a lot of politicians that are afraid of activist pushback if they don’t do something. So they do this, not realizing that this is going to cause us to go backward.”

But the idea the state would “go backward” has a different meaning to advocates who want to see change.

Enoka Herat, ACLU Washington’s police practices and immigration counsel, said people were “slightly disappointed” with the modifications passed this year. Communities of color fear the 2022 rollbacks will mean police can go back to using force in any matter they see fit, she said.

“There wasn’t a single community group that supported this (rollback) bill,” Herat said. “There were thousands of people who reached out to lawmakers to say, ‘Don’t.’”

Steve Strachan, the executive director Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs, said that for him, the new laws address problems with the original reforms – not necessarily erase the effort.

“Some advocacy groups viewed it as a rollback,” said Strachan, whose organization represents more than 800 officers. “I don’t think it was a rollback. I think they were amendments.”

Like many states, Washington has seen a recent uptick in crime, which also affects how the public views policing. Across the state, violent crime, including murder and assault, increased by more than 12% in 2021 from the previous year, according to a July report by the sheriffs and police chiefs association.

Ritter said there’s a direct correlation between hampering police efforts and the jump in crime.

The Rev. Harriet Walden, who serves as a commissioner for the Seattle Community Police Commission, says advocates of police reform were disappointed by the 2022 rollbacks, but they “start organizing and the people want to push back.” (Photo by Olivia Jennings/News21)

“I haven’t seen crime going up this high since the ’80s,” he said. “There is a direct connection … look at the timeline.”

Corry, the Yakima Republican, said the Legislature has more work to do: The 2021 reforms let criminals know they could get away with certain crimes, he said, and now he has heard from residents concerned about public safety.

“Now, we’re starting to hear from them that they want more police response, not less,” Corry said.

Herat refutes the idea that the reforms enabled criminals in Washington.

“There’s a big backlash and emotions are running high,” she said, adding that people shouldn’t blame every crime on police reform.

Lawmakers, law enforcement, activists and community members agreed they’re not done. Several said they’d keep trying to figure out solutions.

Meidl said that since he became chief in Spokane in 2016, he has had to get comfortable having uncomfortable conversations.

“And the same would go the same with those in the community who are frustrated, hurt, angry, scared, nervous,” he said. “They have to be heard and their feelings have been acknowledged, but they have to be comfortable having those uncomfortable conversations as well.”

Kurtis Robinson, Spokane NAACP vice president, said activists can’t stop if they want to see reform. It’s a cycle.

“As soon as any kind of great activist or group of activists comes up in, dominant culture swoops down and takes them out,” he said.

The Rev. Harriett Walden wears two hats. She serves as a commissioner for the Seattle Community Police Commission, which was mandated under the department’s 2012 consent decree to provide community input on police reforms, and co-founded Mothers for Police Accountability. Walden, who has been doing this work for 30 years, said it’s important to include people who keep abreast of issues and people who are willing to organize.

But she recognizes that change comes with hiccups: “The road to police reform is a long road.”

Layla Brown-Clark is a Myrta J. Pulliam Fellow.

Find the full “In Pursuit” project – News21 investigates police reform in America – here.

Our content is free to use. If you want to republish this story, find our terms of use here and download the text story and assets.