Canadian center serves as bridge between First Nation communities and police

Sept. 29, 2022

VANCOUVER, Canada – Law and order for Indigenous people in Canada is one-sided, Norm Leech says.

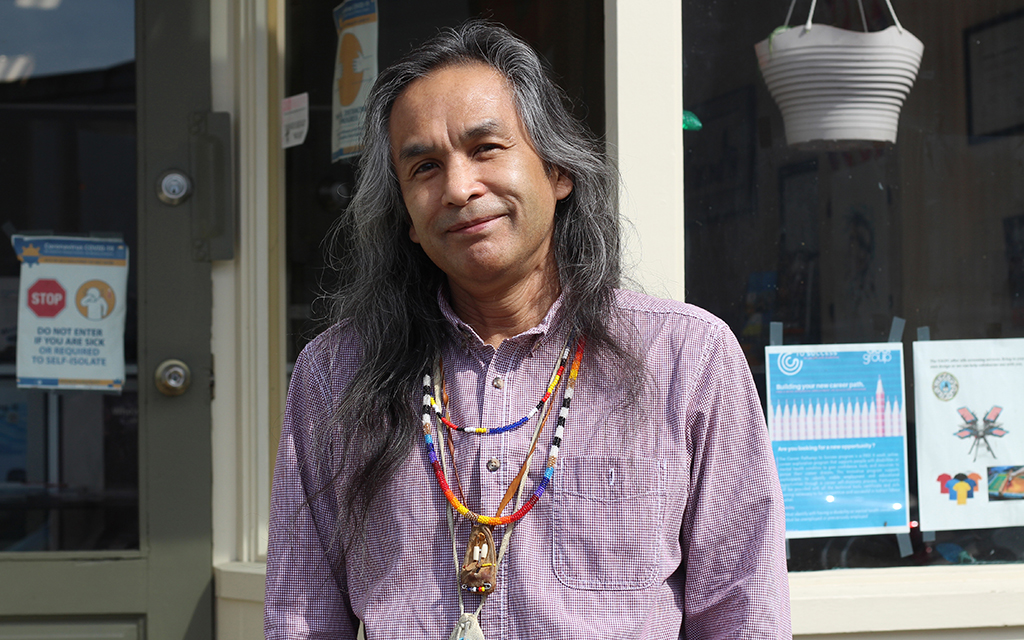

“It’s not about justice because Indigenous people – especially urban Indigenous people in Canada – know that it was never designed or intended to provide justice to us,” said Leech, an activist for First Nation people in British Columbia.

“All these laws were written to police us.”

European settlers founded this Pacific Ocean seaport on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh people.

A 2021 report from British Columbia’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner said Indigenous and Black people are “grossly or significantly overrepresented” in arrests and chargeable incidents across unceded territories.

(Audio by Arrthy Thayaparan/News21)

Community leaders have said the data is an example of over policing and have demanded reform, according to media reports. The tense relationship between Indigenous peoples and police has gained attention and made headlines.

Leech has spent the past six years trying to bridge that gap. He is from T’it’q’et, a St’át’imc Nation community that’s a four-hour drive north of Vancouver.

As a favor for a friend, Leech joined the Vancouver Aboriginal Community Policing Centre, which raises awareness about Indigenous issues and serves as a bridge between urban Indigenous people and the Vancouver Police Department. He’s now the center’s executive director.

Leech said it’s important for everyone to know that policing center staff members are not officers.

“It affects the way people respond to us if they think we’re the police,” he said. “The relationship between Indigenous people and police is not one of trust and friendship and cooperation. It’s one probably more of fear, suspicion and hatred than anything else. But it’s also one of our mandates to try and improve” that relationship.

The center serves nearly 70,000 urban Indigenous people who live in Vancouver, many of them far from their traditional homes, resources and families. It conducts guided medicinal workshops to provide traditional healing for people who need it.

The nonprofit Vancouver Aboriginal Community Policing Centre in Vancouver, Canada, was created to address social justice issues, improve safety for First Nation people and build a relationship between Vancouver police and Indigenous people. (Photo by Arrthy Thayaparan/News21)

Over the past few years, the thousands of missing and murdered Indigenous people across Canada have become a top priority for the center’s leaders.

This spring, as Leech shuffled through a box of herbs to prepare for a workshop, he said he always feels the eyes of the missing on him. Their pictures hang on a bulletin board overlooking his office.

“We search for missing women, we find missing women, we help get them home, we help them get help,” Leech said. “Not only women, but girls, boys and men. There’s a lot of people in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver where it’s easy to disappear … whether voluntarily or not.”

Leech said changes are coming, but they will take time.

“We’re in the best position to be able to influence positive change on policing, not only in Vancouver but in this country,” he said. “The conversation is respectful, and it’s ongoing, and it’s mutual (with the police). … It’s not fraught with conflict, disagreement or contention, but it is slow, and it requires a lot of people to agree to everything.”

Building a relationship between police and Indigenous people is just one aspect of a larger effort.

In 2014, the Vancouver City Council approved a plan for reconciliation with First Nation communities. The city vowed to become a “City of Reconciliation” by acknowledging it was built on unceded land; developing affordable housing that prioritizes Indigenous women-led families; and recognizing “our systemic foundation in colonialism, white supremacy and racism,” among other actions.

However, during a ceremony later that year, Chief Ian Campbell of the Squamish Nation said he wasn’t sure both sides could agree on a reconciliation framework because of all that has been done to Indigenous communities in the past.

“It is refreshing, as a young person, to stand here and to see that there truly is integrity in the leadership of the relationship between our First Nations peoples and the settlers that have come into this part of the world,” Campbell said. “A hundred years ago, our people were forcibly removed from (what is now) downtown Vancouver. And the hurt that many of our elders carried for many decades. This really is about healing.”

Vancouver leaders acknowledge a lot of work remains to be done.

A top priority for nonprofit Vancouver Aboriginal Community Policing Centre in recent years has been the thousands of missing and murdered Indigenous people across Canada. (Photo by Arrthy Thayaparan/News21)

Come back on Oct. 3, when we start publishing the main News21 “In Pursuit” project.

Our content is free to use. If you want to republish this story, find our terms of use here and download the text story and assets.